Groaning in financial pains may be one of the best ways to describe the plight of the average Nigerian worker about now. In 2011, the Federal Government enacted the minimum wage law that benchmarked the minimum take-home pay of any worker in the federal or state public service at N18, 000 per month, with a caveat that the wage is subject to review every five years. While the FG faithfully complied with the payment of the minimum wage, many states did not. Late last year, following the rapid decline in revenue allocations to states from the Federation Account, a development occasioned by the fall in oil prices, state governors under the aegis of the Nigerian Governors’ Forum (NGF) threatened to either dump the payment of the N18,000 minimum wage or to downsize the work force. At the time the controversy raged, several states owed their workers backlogs of several months of unpaid salaries and allowances. But the FG intervened with bail-out funds for them settle the salary bills. Quite unfortunately, indications presently are that some states that got the funds diverted them to other uses. President Muhammadu Buhari, who hosted members of the NGF last week in Abuja, revealed, for example, that despite the release of bail-out funds to states, about 24 of them were still unable to settle workers’ salaries.

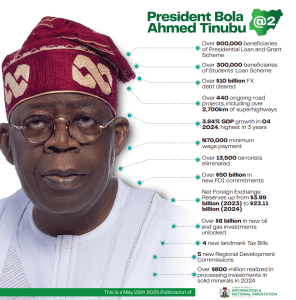

About 27 states reportedly asked for the facility, while a total of N662 billion was provided for the purpose. The government is said to be contemplating yet another round of financial bail-out for distressed states by way of refunding monies they spent on infrastructure repairs and maintenance on behalf of the FG, among others. But amidst the persisting financial mess, organised labour a couple of days to the last Sunday celebration of Workers Day, tabled its demand for N56, 000 as minimum wage, reflecting over 200 percent increase over the subsisting N18,000 minimum wage some states were yet to comply with. Defending the new demand, the President of Nigeria Labour Congress (NLC), Ayuba Wabba, said it was premised on the agreement between government and organised labour that the minimum wage shall be reviewed every five years. Essentially central to the argument in favour of N56, 000 new minimum wage, however, is the eroded value of N18, 000 old minimum wage. In 2011, the nairadollar exchange rate was in the range of N110 to $1. But presently, the rate has soared to over N200 to a dollar. When inflationary pressures that have gone past the two-digit mark and still counting are added to the drop in the value of the old minimum wage, the purchasing power of N18, 000 is further crippled.

Experts also argue that organised labour should worry more, not about huge increases in minimum wage, which they said would be worthless without inflation being pegged at tolerable limits, but about firming up the value of the naira to make the purchasing power of the prevailing minimum wage appreciate sufficiently. In the months ahead, it will be seen how the FG and organised labour will resolve the new wage palaver, since the law says the wage is subject to a review every five years. B

ut it may be said that with the huge salaries and allowances political officeholders arbitrarily allocate to themselves without minding the excruciating pains of workers, the latter’s traumas orchestrated by hunger, depression, privations and hopelessness; massive stealing and the ghost-worker syndrome through which corrupt top bureaucrats outrageously assault government’s coffers and escape with their loot without punishment; as well as general public sector corruption that remains largely untamed as yet, the agitation for an upward review of minimum wage by organised labour did not come to us as a surprise.

Our thinking is that the clamour will not only keep the government on its toes, but will, in addition, encourage the FG to further stretch its anti-graft campaign to plug all leakages, discourage profligacy and wanton wastage of public funds which are provocative to all citizens, including the workforce. From the exasperation demonstrated by workers during the last Workers Day events, it is obvious they have been pushed to the wall by the current avoidable hardships.

A government with the knack for reneging on its word, even after agreements are on paper or enacted as law, is a national embarrassment; just as a country inundated daily by shocking tales of disgusting embezzlement and fraud by top officials that escape with their loot unpunished should not lack funds to sustain the welfare of its workers.