Recently, the Chief Economist at the Economic Commission for Africa (ECA), Hanan Morsy, disclosed that Africa currently accounts for 54.8 per cent of the world’s poor. Speaking at the 55th session of the Conference of Africa’s Ministers of Finance, Planning and Economic Development in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Morsy lamented that since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the continent has experienced monumental global shocks that have worsened existing socioeconomic operations. The development has led to the continent having more than half of people in extreme poverty the world over.

Of the world’s estimated population of eight billion people, Africa accounts for 1.4 billion, with Nigeria having the highest on the continent, followed by Ethiopia, DR Congo, Egypt and South Africa. According to the latest global data, 85 per cent of the world’s population live on less than $30 per day. The figure is much less in Africa.

As at 2022, 23 per cent of the global population (1.8 billion people) were living on less than that threshold. In Africa, it is estimated that 548 million out of the total population of 1.4 billion lived in extreme poverty as at last year, and 149 million people are at risk of falling into poverty this year. The ECA Chief Economist says that the situation in Africa has been exacerbated because of the skewed distribution of wealth and inequalities across the continent. The situation is worse in East and West Africa, which have the higher share of the continent’s poverty.

Overall, South Sudan has the highest share of population living in extreme poverty in Africa, at 82 per cent, followed by Equatorial Guinea, 76.8 per cent, Madagascar, 70.70 per cent, Malawi, 70 per cent, Guinea Bissau, 69.3 per cent, Eritrea, 69 per cent, Sao Tome and Principe, 68.7 per cent, Burundi, 64.9 per cent, Democratic Republic of Congo, 63 9 per cent, and Nigeria, 63 per cent. Nigeria’s case is the worst because it is estimated that only five per cent of the population controls the nation’s wealth. The growing poverty in Africa is dangerous and can breed discontent and social unrest

We share the remedy suggested by Morsy that there is need for governments in Africa to vigorously and genuinely pursue inclusive macroeconomic policies that will target the poor and the most vulnerable in the society. In addition, there is need to build efficient and resilience institutions with the capacity to withstand future shocks at the household and community levels. Beyond that, African countries need to harness their resources for the collective good of the people.

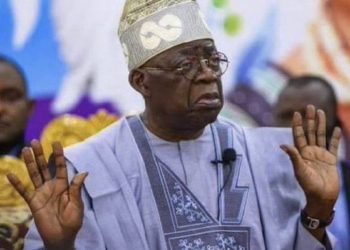

However, it must be said that most African countries found themselves in the poverty hole as a result of failure of governance. For instance, many Nigerians are poor because of corruption induced by bad governance. Sadly, measures put in place to address the scourge are not enough. The 2022 poverty index by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) put 133 million or 63 per cent of Nigerians as being extremely poor.

Also, the attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) may be truncated in view of the rising poverty on the continent. While African leaders are not short on promises, they are not forthcoming with delivering them. The situation in Nigeria is perhaps a replica of what obtains in most African countries.

Having 133 million poor people shows that the outgoing federal government has really lost the battle against poverty despite the huge investment in many poverty intervention programmes. President Muhammadu Buhari’s promise to lift at least 10 million people out of poverty annually remains unfulfilled. Regrettably, about six million Nigerians enter into the poverty net yearly.

Official corruption is one of the triggers of poverty in Africa. For example, the 133 million poor Nigerians by the NBS exceeded the World Bank’s projection for the country in 2022, as well as that of many African countries. The World Bank had in 2022 stated that poverty reduction stagnated since 2015, and projected that the number of poor Nigerians would hit 95.1million in 2022.

The poverty rate released by the ECA should be seen as a ticking time bomb, which may explode with dire consequences, if not timely addressed through good leadership, sustainable investment in human capital development and others. Revamping the economies of African countries will create more jobs, stimulate growth and enhance the wellbeing of their citizens.