When President Bola Tinubu ended the fuel subsidy during his inauguration on May 29, 2023, it was hailed as a bold and necessary step toward fiscal reform.

The move promised to free trillions of naira from an unsustainable subsidy regime, redirecting these funds to critical sectors such as infrastructure, education, and healthcare that have long suffered neglect.

Nigerians were assured that this sacrifice would translate into real, tangible improvements in their daily lives.

Yet, two years on, this promise remains largely unfulfilled. Despite a historic surge in government revenues, the average Nigerian has yet to feel the benefits.

In 2024, the Federation Account Allocation Committee distributed N28.78 trillion to the three tiers of government, representing a 79 per cent increase from the previous year. This was mainly due to the removal of fuel subsidies and adjustments in exchange rate policies.

State governments saw their allocations jump by 45.5 per cent to N5.22 trillion. Even as recently as May 2025, monthly distributions exceeded N1.6 trillion, marking a 72 per cent increase compared to the same period two years earlier.

Such an influx of funds should have offered a once-in-a-generation opportunity for states to reset their development priorities and invest in the foundations of growth.

Instead, Nigerians continue to grapple with dilapidated infrastructure, underfunded schools, inadequate healthcare, and a worsening poverty crisis.

According to a joint report by the World Bank and Nigeria’s National Bureau of Statistics, over 129 million Nigerians now live below the poverty line, an increase of 25 million in just one year.

The World Economic Forum’s 2024 rankings place Nigeria 130th out of 141 countries in infrastructure quality, underscoring the yawning gap between resources and results.

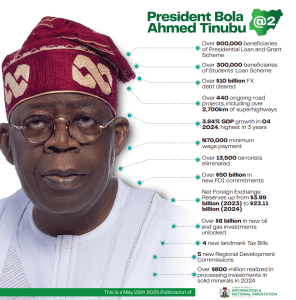

Where, then, has all the money gone? The National Orientation Agency asserts that the savings from subsidy removal have funded major investments, including a N20 trillion infrastructure fund, student loans through NELFUND, and substantial allocations to agriculture and solid minerals.

On Monday, Tinubu pointed out that the Federal Government has directed N4 trillion saved from the petrol subsidies to infrastructure.

Yet, the reality on the ground tells a different story. Many state governors have reverted to familiar patterns of waste and self-indulgence, lavishing public funds on fleets of luxury SUVs, needless travel, grandiose government buildings, and headline-grabbing projects that do little to alleviate the daily struggles of ordinary Nigerians.

In some states, new airports and conference centres have sprung up even as rural clinics lack basic medicines and schools remain dilapidated.

The much-needed increase in the national minimum wage to N70,000 has been met with resistance, with many states either failing to pay or doing so inconsistently.

Relief programmes designed to cushion the impact of subsidy removal have been poorly coordinated and insufficient, leaving millions to bear the brunt of rising costs.

To worsen such abysmal misgovernance, 10 states collectively increased their domestic debt by N417.7 billion from N884.9 billion in Q1 2024 to N1.3 trillion in Q1 2025, despite increased FAAC allocation per DMO data.

Public frustration is palpable. A 2024 Afrobarometer survey found that 62 per cent of Nigerians believe the removal of the petrol subsidy has worsened their living conditions, while only 18 per cent think the savings are being used effectively.

This widespread perception of squandered opportunity echoes the cautionary tale of the Excess Crude Account, established in 2004 to save surplus oil revenues. Once holding over $20 billion, the ECA was depleted to a mere $2 billion by 2015, largely due to unchecked withdrawals instigated by state governors. As of April, the ECA balance stands at under $500,000.

Economists warn that Nigeria risks repeating past mistakes by prioritising consumption over investment, leaving itself vulnerable to future economic shocks.

It is becoming increasingly clear that unless state governors are held accountable and compelled to invest in people, infrastructure, and essential services, the cycle of poverty and underdevelopment will persist, no matter how much money flows into government coffers.