For a heavily indebted country and its constituent states struggling with their economies and development, the unrelenting agitation for more states is misguided and atavistic.

Therefore, the current proposals before the National Assembly to create 31 new states from the existing unproductive and unsustainable 36 states to make 67 states are symptomatic of a political class that is unserious about nation-building, especially given Nigeria’s already skewed federalism.

Faced with unending agitation since the start of the Fourth Republic, every NASS has unsuccessfully attempted state creation. The reason is lost on the parliament: federalism grows sustainably when its fundamentals are in operation.

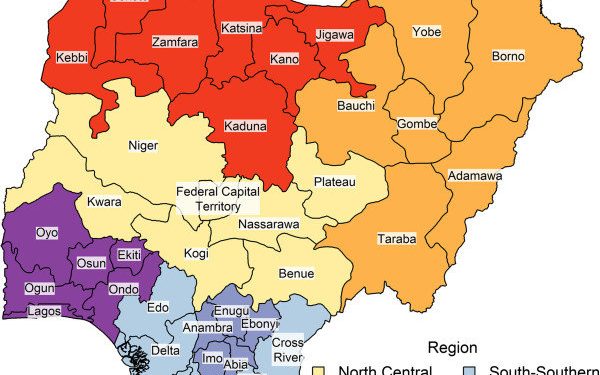

Nigeria’s experience during the Independence and Republican eras underscores the strength of true federalism: a lean central government, robust and autonomous regions, productive governments, healthy competition, respect for diversity, and an abiding commitment to the unity and distinctiveness of each region.

Where these principles were upheld, good governance, peace, and development followed. Only the Mid-Western Region was created primarily due to the political dynamics between the North and Obafemi Awolowo’s progressive Western Region.

In 1960, federalism flourished in Nigeria, as distinct regions shared powers with the centre. Power was devolved, ensuring regional autonomy, with 45 items on the Exclusive List and 26 on the Concurrent List. Each region managed its resources—groundnuts in the North, cocoa in the West, palm products in the East, and the Mid-West—and grew at its own pace.

By 1963, the regions had their constitutions, fuelling competitive and sustainable governance. This ended in 1966 when the military seized power, collapsing Nigeria’s federal system into a unitary one—an event whose repercussions continue to haunt the country.

The key features of federalism were undermined. As a result, the competition for more states and increasing problems began. The regions were later replaced by states. The military established 12 states in 1967, 19 states in 1976, 21 states in 1987, 30 states in 1991, and 36 states, along with the FCT, in 1996.

This atomisation reflected on the economy. Oil was discovered in commercial quantities. Agriculture, the mainstay of the economy, and the competition that came with it were abandoned.

The allocation formula that required states to retain 50 per cent of their resources, put 30 per cent into the Distributable Pool, and 20 per cent to the centre was upturned. Conversely, the states and the LGs became subservient to the centre.

The robust concurrent list was reviewed in favour of the centre, and states were turned into monthly rent-seekers. It marked the end of economic and development competition and the beginning of corruption and bad governance, culminating in the relentless agitation for more states.

The creation of states under the military was easy because it was done by fiat. It has, however, been a nightmare since the advent of the Fourth Republic in 1999.

The implications of the creation of more states are legion. It amounts to more states, more troubles.

Besides the cumbersomeness, the economic volatility of the existing 36 states and the FCT, and the vertical allocation sharing formula of 52.68 per cent to the Federal Government, 26.72 per cent to the 36 states, and 20.60 per cent to the 774 LGs make state creation impractical and unreasonable.

An expanded state structure would see the Federal Government—largely unproductive—retain the lion’s share, while a larger cohort of states squabble over an already insufficient share.

This will exacerbate social chaos, deepen poverty, and multiply cost centres at the expense of development.

The recent request by Lagos Governor Babajide Sanwo-Olu for the inclusion of 37 LCDAs in the Constitution partly highlights the danger: such moves would overwhelm the allocation pool and trigger copycat demands nationwide. The states are after their own, because the higher the number of LGs a state has, the higher its allocations from the centre.

An indebted, low-productivity country like Nigeria does not need new states. As of March, states and the FCT had racked up N3.86 trillion in domestic debt. A 2022 report flagged six states, including Katsina, Taraba, and Yobe, as insolvent.

The cost of running state bureaucracies is enormous. Between 2018 and 2019, states’ spending rose from N5.12 trillion to N5.26 trillion, with recurrent expenses and loan repayments accounting for an ever-larger share.

The pattern is clear: More states breed more corruption. Under President Olusegun Obasanjo, the EFCC alleged that 12 governors were enmeshed in corruption.

Now, the EFCC Chairman, Ola Olukoyede, says 18 of the 36 governors are under corruption investigations.

Many states struggle to pay the minimum wage, and others have yet to comply. The National President of the Nigeria Union of Teachers, Haruna Kankara, said in April that 20 states had yet to implement the N70,000 minimum wage for LG workers and primary school teachers.

Most governors have refused to judiciously utilise the increased allocations accruing to them on account of the fuel subsidy removal and floatation of the naira. They splurge on state airports, convoys of vehicles and aircraft. This suggests that states creation is pyrrhic.

Infrastructure development is another casualty. The World Bank Country Director, Nigeria, Shubham Chaudhuri, said that “public spending at both the federal and sub-national levels has been very low.”

Nigeria requires between $100 billion and $150 billion annually over the next 30 years to close its infrastructure deficit. By World Bank accounts, 87 per cent of Nigeria’s 200,000km roads are in deplorable condition. The state roads constitute a part of this network. How does the creation of more states surmount these challenges?

The creation of more states will shoot election costs to the high heavens and pile enormous pressure on the fragile economy. INEC says it received N313.4 billion for the 2023 general elections. The electoral body proposed N126 billion for the 2025 by-elections alone.

State creation is not a cure for Nigeria’s chronic problems of unemployment, economic stagnation, insecurity, poverty, or misgovernance. It is a shortsighted, populist move that will keep the country stagnant.

With hindsight, the productive regionalism of the First Republic, with four regions, was more prosperous than the unproductive 36-state structure. This is proof that system fundamentals and good governance, not mere structure, matter most.

It is for good reason that the US retains its 50-state structure, Canada its 10-province and three-territory structure, Australia its six-state and two-territory parliament structure, and Germany its 16-lander structure. Nigeria must study why these federal states retain their structures.

Sharing allocations is strange to the federal system, or any system of government, for that matter. Nigeria has been a laughing stock for too long. Governments are created to produce and manage resources, not to engage in rent seeking. The country must have a good governance model that will be productive, good governance-inclined, and development-savvy.

Consequently, the NASS should stop politicising governance. It should tell the people the truth and do the needful.

As the Abia State Governor, Alex Otti, rightly observed, “The country doesn’t require additional states, especially when most of the existing states lack the viability for economic self-sustainability.” This is leadership. This is courage. Other Nigerian leaders must follow this example.

As the experience with federalist states shows, productive, dually sovereign, well-governed, autonomous, and competitive states are the strength of federalism and democracy. This is what Nigeria’s political leaders should pursue, not more burdens.

True federalism, not endless fragmentation, offers the way forward.