- Exam malpractice and certificate forgery need new solutions

- Exam malpractice and certificate forgery need new solutions

As Nigeria struggles to combat the twin evils of examination malpractice and certificate forgery, it must seek new and innovative approaches if it is to reduce them to the barest minimum.

The seriousness of the country’s predicament was driven home by the possibility of the Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board (JAMB) resorting to the use of mobile courts for exam cheats and recent arrests of unqualified graduates by the National Youth Service Corps (NYSC).

A former Registrar of JAMB, Mr. Bello Salim, advised the board to facilitate the establishment of specialised mobile courts in order to deal with those involved in examination malpractices in an expeditious fashion. Arguing that the immediacy of the digital age had aggravated the problem, Salim stated that JAMB’s processes needed to respond with similar alacrity.

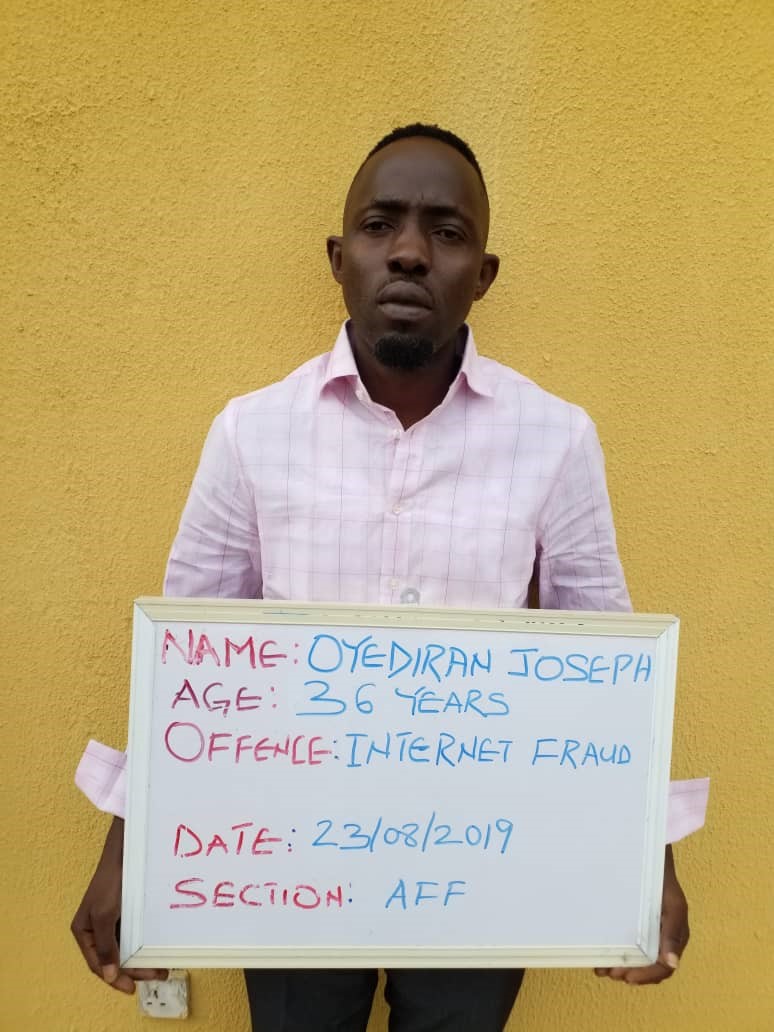

The NYSC’s identification and arrest of nine unqualified graduates in Katsina, Kebbi and Taraba states brings the number of culprits caught to 50 for the Batch B Stream Call-up alone. Many claimed to have graduated from unrecognised universities outside Nigeria, or were in possession of fake certificates and verification documents from authentic Nigerian universities.

Examination malpractice and certificate forgery are perhaps the greatest threats to the development of Nigeria’s human resource base. They compromise the integrity inherent in the educational process, cast doubt on the qualifications of honest graduates, and undermine the capabilities of the country’s workforce.

It is no surprise that many observers are recommending a stronger response to these issues. Mobile courts would certainly speed up a process that has been characterised by a ludicrous slowness, worsened by overly-sympathetic policing and a clear reluctance to follow laid-down regulations.

While much of this tardiness can be attributed to corruption, there is also the perceived harshness of the punishments prescribed for examination malpractice and certificate forgery. The Examination Malpractices Act of 1999 is Nigeria’s main legislation dealing with examination malpractice and certificate forgery. The Act covers cheating in exams, the theft and sale of question papers, impersonation, conduct during examinations, conspiracy and corporate offences.

Cheating, stealing question papers, impersonation, and tampering with documents attract a fine of N100,000 or a maximum of three years’ imprisonment, or both. If the culprit is a teacher, supervisor, examiner or employee of the examination body, the punishment is a four-year jail term without the option of fine.

Disorderly conduct during an examination will result in fines of N50,000 upon conviction. Inciting disturbances and forgery attract fines of N100,000 or three years’ imprisonment, or both. Persons in positions of authority will receive a five-year jail term without the option of fine.

It is obvious that, in spite of its avowed good intentions, the Act is deeply flawed. It is unbalanced; the ridiculously light fines are opposed to draconian prison terms, thereby making arbitrary outcomes almost inevitable. “Disorderly conduct” and “inciting disturbances” are virtually synonymous but attract different penalties.

The Act prescribes punishments for individuals “under the age of 18 years” but still requires that persons who are yet to attain the age of 17 years of age be dealt with under the provisions of the Children and Young Persons Act. Thus, a few months’ difference in age could result in very different consequences for culprits. We would want to suggest here however that minors caught in the web of exam malpractice should be given custodial sentence, especially if they are first offenders. This is to prevent a situation where such minors are locked up with hardened criminals, thus making them worse when exiting the prison than when they went in. But the ‘professional exam writers’ who make money from the ‘enterprise’ should have more severe punishment. The same should apply to parents who condone or facilitate such crimes for their children. If the proposed mobile court takes off, there should be provision for appeal to minimise the possibility of miscarriage of justice.

Moreover, we observed that little allowance is made in the Act for the perpetration of digitally-facilitated malpractices. Disturbances at examination venues, for instance, might be virtual rather than strictly physical occurrences; social media has redefined the extent and intensity of conspiracy beyond traditional notions of the term.

Such anomalies are a clear indication that more emphasis should be placed on preemption and rehabilitation, as opposed to punishment.

If it becomes less-easy to get away with examination malpractice and certificate forgery, fewer will attempt it. If the punishments for these offences are properly calibrated to their gravity and speedily carried out, more potential culprits will realise that their actual disadvantages outweigh any potential benefits. If offenders are made to see the error of their ways, they will be less likely to engage in repeat behaviour in future.